Alliance for Suicide Prevention of Larimer County training thousands of youth, adults to spot and prevent suicide

Declines in suicide rate in recent years attributed to community-wide collaboration

NOTE: This Spotlight article appeared in the Oct. 28, 2025, edition of The Lamplighter, Larimer County Behavioral Health Services' newsletter.

Not all superheroes wear capes.

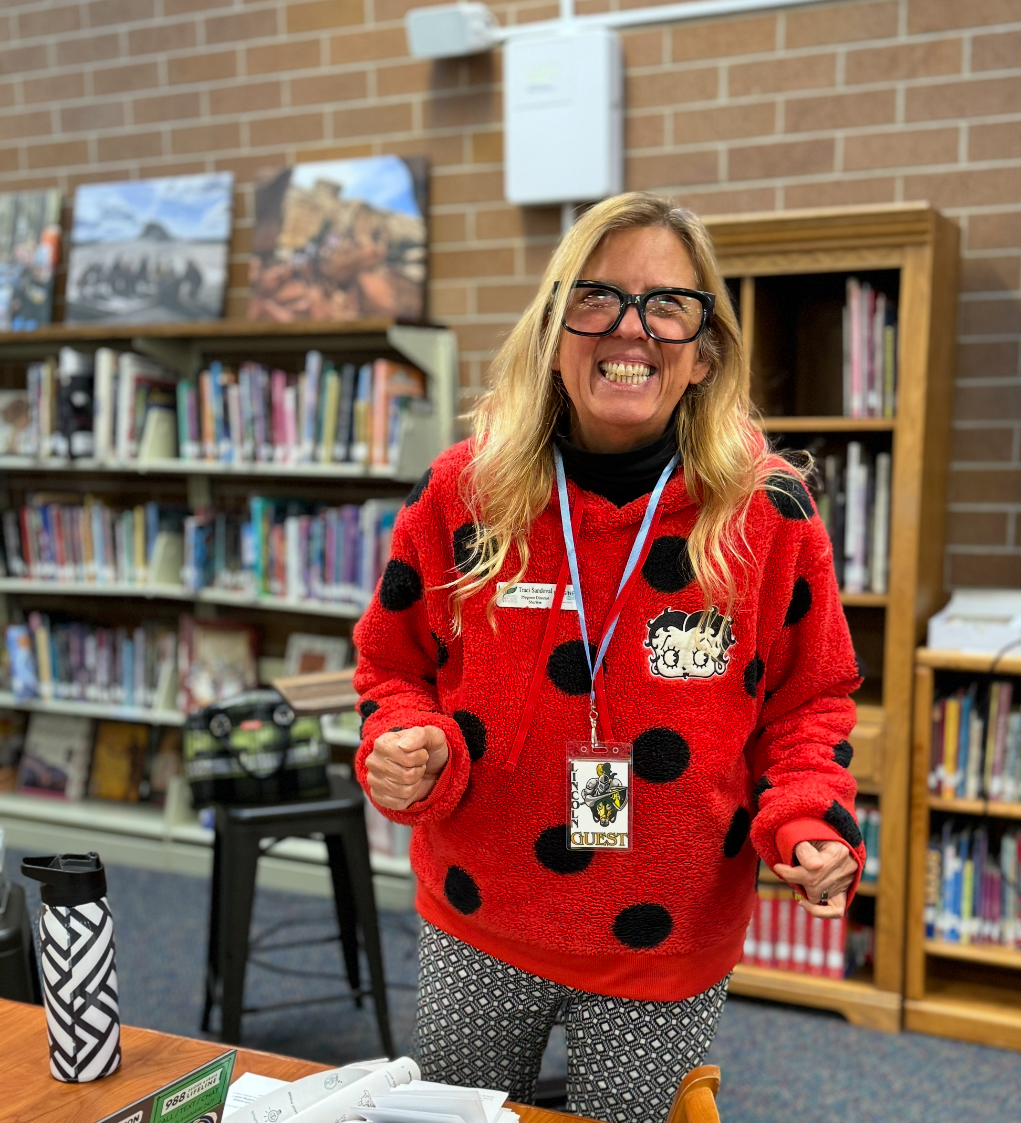

Take Traci Sandoval, for example. She uses her powers of self-described spastic energy, adolescent humor, and expertly refined lessons to save lives.

While scrolling around on LinkedIn after the COVID pandemic, Sandoval saw an opening with The Alliance for Suicide Prevention of Larimer County.

For the former neuroscience researcher and middle school Science educator, who studied positive psychology in college, teaching secondary students how to prevent suicide seemed like the perfect fit. That’s where Sandoval’s journey with REPLY began.

Resiliency Education Protecting the Lives of Youth, or REPLY, is a free suicide prevention program available to all middle and high school youth in Larimer County. The program was started by the Alliance in 1992 and is funded, in part, by taxpayer dollars. The Alliance has been awarded nine grants through Larimer County Behavioral Health Service’s annual Impact Fund Grant Program, including some crisis funds related to pandemic-era efforts.

Sandoval used to live in Texas, where lawmakers decide how to spend tax dollars. She feels fortunate to be in Larimer County now, where voters decided in 2018 that 25 cents of every $100 spent should be invested in behavioral health.

“How cool is that? I’m not from a place like that,” she said. “I can’t believe we’re here. What a magical place we’re in.”

REPLY program in action

What is the secret to happiness?

Sandoval once taught a middle school “Habits of Happiness” class and told students to “just choose it.” Her mother was a motivational speaker who believed one shouldn’t think negative thoughts because it’s possible to manifest happiness.

Then, both of Sandoval’s parents died, and she realized it wasn’t a choice.

A student helped her see the importance of their deaths and the complexities of grief.

“Now, I don’t just talk about coping but how hard that can be. I am so grateful to her for sharing that insight and her understanding of severe sadness,” Sandoval said.

Over the past five years, Sandoval and a team of interns have continued to refine and improve the REPLY program. What started as something focused more on mental health diagnoses has morphed into engaging discussions about how hard day-to-day life can be, the chemistry of their developing brains, positive psychology, building trust with adults and friends, and identifying and preventing suicide.

“Tracy is so authentic. Her super power is middle school students,” said Lawrence Hermance, a trainer, grant writer, and peer support member with the Alliance. The former Army veteran knows more more people who have died by suicide after their service than those who lost their lives because of it.

When he started at the Alliance, he taught the REPLY program with Sandoval and appreciated the program’s focus on normalizing puberty, depression, and more.

What has surprised Sandoval most is the students’ candor.

At her very first REPLY class at a high school in Loveland, a young woman told roughly 60 other students she wasn’t in the class, or even in the same grade. She went to the class each year to remind herself that she’s alive and what’s at stake after her own suicide attempt.

“We definitely share difficult stories in the classroom,” said Sandoval, who at age 29 lost her best friend to suicide. “Whenever we get feedback from students, one common theme is that students love the stories. Stories are the real life of what’s going on … they make us feel things in a way that information alone does not.”

They love the stories. That and her spastic energy, she says, laughing from behind chunky black glasses.

Caroline Dusett works for SummitStone as an overnight clinician at the Acute Care facility at Longview campus. Before that, she interned with Sandoval.

Dusett grew up on the East Coast where suicide wasn’t discussed in schools. “They believed if you didn’t talk about it, it didn’t happen,” she said.

She was surprised then, to find that students in her REPLY classes were open to talking about behavioral health and already fairly educated about suicide. Larimer County is doing great, “offering things to kids that were never offered to me,” said Dusett, who loves watching adolescents grow and being a part of positive change in the community.

Jacque Kinnick is a Social Studies and Health teacher at Webber Middle School in Fort Collins. In 20 years, she has seen the REPLY program evolve – and so much more now that Sandoval has figured out how to keep students engaged in the heavy topic. It’s become a consistent and relied-upon resource.

“We know that kids have thought about it (suicide), and talking about it can actually save lives,” said Kinnick. “This program allows kids a space to hear that information and have an understanding of what they can do with that information.”

Which is key, because so many people have a connection to suicide, she said, whether through a friend, someone in their family, or themselves.

At the end of each REPLY class, students are asked to anonymously write down the name of someone who may need help. It could be a friend, a classmate, or themselves. On average, 12% of students reach out for help immediately following a presentation. Staff then follow up with those students.

“I do know that kids are reaching out. I do know kids are getting the help they need,” she said, emphasizing the positive impact REPLY has had.

“Being in a community that prioritizes prevention, that prioritizes support and resources helps reinforce to students that none of us is alone,” Kinnick said. “We want to help students to navigate the challenges they face.”

“Just being in a community that values taking care of our kids, makes me very proud,” she later added.

Larimer County’s history with suicide

This region is widely considered a desirable place to live, work, and play. It is close to the mountains, boasts ample outdoor recreation, and has strong PK-12 and university education options. Fort Collins, one of the cities within Larimer County, has frequently been rated among the top places to live – in Colorado and across the nation.

More people are moving here from areas within Colorado – the top five are Adams, Boulder, Denver, Jefferson and Arapahoe counties, the Larimer County Economic & Workforce Development reported at its September symposium. Second to that, are those from Texas, California, and Wyoming.

People want to be here. Yet, Larimer County – and Colorado – have historically had some of the highest rates of suicide.

No one really knows why. But there are lots of theories.

Some speculate it could be the altitude, while others say it’s tied to a Western mentality where ‘you pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’ rather than ask for help. It may be mental health or substance-use issues that go unaddressed or are insufficiently treated. And for others, their dreams and realities didn’t sync up; they weren’t living the idyllic life they envisioned in one of the best places to live.

Larimer County has experienced the ripple effects of adolescent and adult deaths by suicide for years, data on the health department’s public dashboard show. In the early 2000s and prior, different organizations were educating people about how to prevent suicide and help those in need.

Then, about a decade ago, the call for change grew louder, perhaps, than ever. Of the 81 suicide deaths in 2015, four were youths, including two as young as 11. The community was shaken – and motivated to act.

In the years since, there have been a proliferation of efforts to address these preventable deaths. There are too many to name here, but a few include:

- Larimer County’s three school districts invested in more mental health staff and social-emotional learning, and deepened partnerships with the Alliance for Suicide Prevention.

- Question, Persuade, and Refer, or QPR, training is adopted as an evidence-based practice for suicide prevention. Thousands of people in this community have learned to recognize the signs of suicide and act in a mental health emergency.

- Larimer County voters passed a dedicated behavioral health sales tax in 2018.

- A Suicide Fatality Review Board formed to review suicide deaths, learn the best ways to prevent them, and use data to enhance community health. Learn more in the Larimer County Community Health Improvement Plan.

- The Imagine Zero coalition was born in 2015 in direct response to the youth deaths. It brings together professionals, agencies, and community members who strive to build a wider and stronger safety net of suicide-prevention resources in Northern Colorado.

- Larimer County also joined the Colorado National Collaborative (CNC), a project that includes more than 14 other Colorado county partners, as well as state and national stakeholders. All are working to reduce suicide death through a data-driven and collaborative public health approach.

- In 2024, the Larimer County Coroner’s Office added a family advocate to its team, an innovative and novel position among coroner and medical examiner offices. This new addition to the profession ensures compassionate and empathetic follow-up to families and community members affected by a death. Family advocacy provides a proactive grief support check-in and connection to local resources and partnerships. It is also a safe place for families to have someone to speak to and be heard no matter where they are in their grief journey. Additionally, through its partnership with the Alliance for Suicide Prevention, the Coroner’s Office distributes grief support kits for adults and children known as a "hug-in-a-box." These are designed to help families navigate their grief, understand they are not alone, and know they matter.

To gauge the success of suicide prevention work, the 2019 Larimer County suicide death crude rate was established at 23.0 per 100,000 residents.

Fast forward four years, and there was a nearly 30% reduction in the rate, to 16.5 suicide deaths per 100,000 residents. There were 61 suicide deaths in Larimer County in 2023, the lowest number of deaths in the county since 2013.

Asked why she thought it declined, Alliance Executive Director Kim Moeller credited the community’s approach to collaboration.

What’s different about Larimer County, she said, is that people solving this problem together have longevity in their positions. They have not just built but grown partnerships, which allow them to go deeper and deeper with these efforts.

Where we go from here

Between 2022 and 2023, there was a decline of 17 deaths. That was followed by a climb from 61 deaths in 2023 to 84 deaths in 2024.

These numbers are difficult to consider, in recognition of the lives they represent and the number of people in our community impacted by tragic loss.

Wider data trends offer a slightly more positive outlook. The average of 2023 and 2024 is 72.5 suicide deaths, which is the lowest two-year average in over a decade. It is a slight declining trend that requires the community to continue working to reduce suicide deaths.

It’s “tricky,” Hermance said.

“It can make you lose hope when numbers rebound,” he said, sitting with Moeller in the Alliance office, which is co-housed with other organizations in the United Way of Larimer County building on West Oak Street in Fort Collins.

“But it makes me realize we need to broaden our perspectives,” he said. This means that there’s more to learn about the factors contributing to suicide that are, ultimately, as complex as the individuals themselves.

Moeller shared a similar view.

“It just tells us the work isn’t done. The community is always changing. We’re always going to work toward hope and healing,” she said.

To learn more about the Alliance’s programs, free training, and initiatives, visit www.allianceforsuicideprevention.org/

What the Alliance will use 2025 grant dollars for |

|

Alliance for Suicide Prevention of Larimer County's free suicide education and support programs | Resources for Men: Grounded Generations |

|

|

Need urgent behavioral health care?

- Call the SummitStone Crisis Center, 24/7/365, at 970-494-4200

- Call or text 988 to reach the 988 Colorado Mental Health Line

- Go to the behavioral health urgent care on the Longview campus at 2260 W. Trilby Road in Fort Collins.

Madeline Novey

Communication Coordinator

Behavioral Health Services

970-619-4255

noveyme@co.larimer.co.us